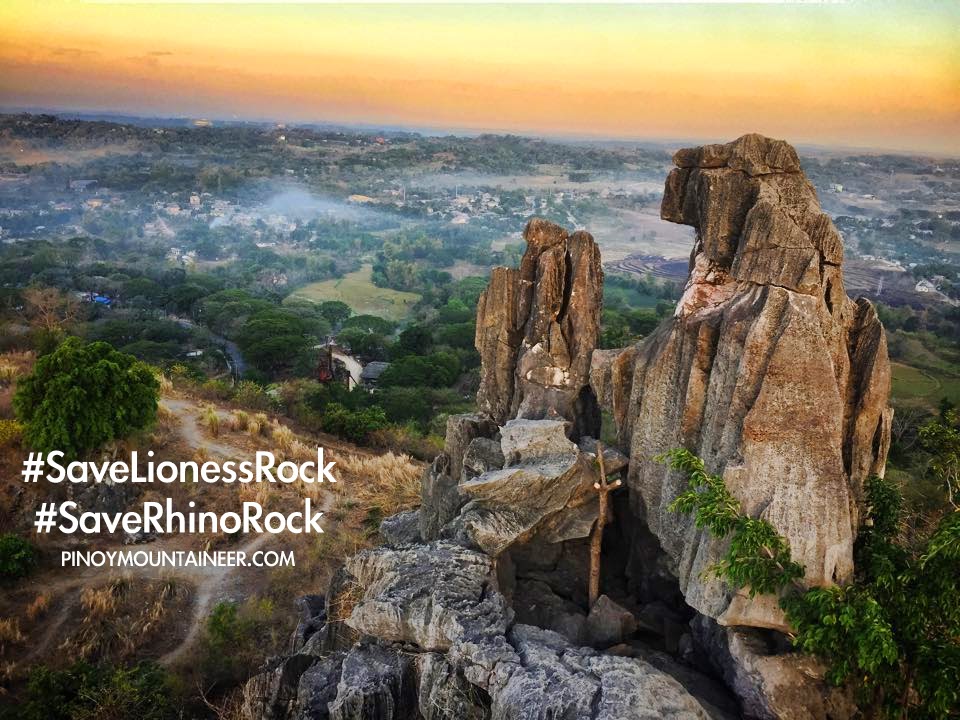

![]() |

| View from Mt, Isarog's summit, where Fedor Jagor said he camped in 1859 |

annotated by Gideon LascoIn the course of my historical research I have stumbled upon various accounts of mountain climbing trips in the journals of hikes in the Philippines - or at least descriptions of various mountains. They are too interesting to ignore so I thought it would be nice to start a series about them. ![]() |

| Fedor Jagor (1816-1900) |

The first on our list is Fedor Jagor (1816–1900), a German scientist and explorer who traveled in the Philippines from 1859-1860. This account is probably the first to describe hikes up Bicol mountains. It also references the first ascent of Mayon -- apparently by two men from Scotland. I like the way these chroniclers of bygone years are so detailed with their notes. There is also some personal touch too, when he said: "I sprained my foot so badly in ascending Mayon that I was obliged to keep the house for a month."MT. ISAROGThe Isaróg (pronounced Issaró) rises up in the middle of Camarines, between San Miguel and Lagonoy bays. While its eastern slope almost reaches the sea, it is separated on its western side by a broad strip of inundated land from San Miguel Bay. In circumference it is at least twelve leagues; and its height 1,966 meters.1 Very flat at its base, it swells gradually to 16°, and higher [191]up to 21° of inclination, and extends itself, in its western aspect, into a flat dome-shaped summit. But, if viewed from the eastern side, it has the appearance of a circular chain of mountains rent asunder by a great ravine. On Coello’s map this ravine is erroneously laid down as extending from south to north; its bearing really is west to east. Right in front of its opening, and half a league south from Goa, lies the pretty little village of Rungus, by which it is known. The exterior sides of the mountain and the fragments of its large crater are covered with impenetrable wood. Respecting its volcanic eruptions tradition says nothing.

This hillock, as well as the others which I examined, consisted of the débris of the Isaróg, the more or less decomposed trachytic fragments of hornblende rock, the spaces between which were filled up with red sand. The number of streams sent down by the Isaróg, into San Miguel and Lagonoy bays, is extraordinarily large. On the tract behind Maguiring I counted, in three-quarters of an hour, five considerable estuaries, that is to say, above twenty feet broad; and then, as far as Goa, twenty-six more; altogether, thirty-one: but there are more, as I did not include the smallest; and yet the distance between Maguiring and Goa, in a straight line, does not exceed three miles. This accounts for the enormous quantity of steam with which this mighty condenser is fed. I have not met with this phenomenon on any other mountain in so striking a manner. One very remarkable circumstance is the rapidity with which the brimming rivulets pass in the estuaries, enabling them to carry the trading vessels, sometimes even ships, into a main stream (if the expression may be allowed), while the scanty contributions of their kindred streams on the northern side have scarcely acquired the importance of a mill-brook. These waters, from their breadth, look like little rivers, although in reality they consist of only a brook, up to the foot of the mountain, and of a river’s mouth in the plain; the intermediate part being absent.

The country here is strikingly similar to the remarkable mountain district of the Gelungúng, described by yet the origin of these rising grounds differs in some degree from that of those in Java. The latter were due to the eruption of 1822, and the great fissure in the wall of the crater of the Gelungúng, which is turned towards them, shows unmistakably whence the materials for their formation were derived; but the great chasm of the Isaróg opens towards the east, and therefore has no relation to the numberless hillocks on the north-west of the mountain. Behind Maguiring they run more closely together, their summits are flatter, and their sides steeper; and they pass gradually into a gently inclined slope, rent into innumerable clefts, in the hollows of which as many brooks are actively employed in converting the angular outlines of the little islands into these rounded hillocks. The third river behind Maguiring is larger than those preceding it; on the sixth lies the large Visita of Borobod; and on the tenth, that of Ragay. The rice fields cease with the hill country, and on the slope, which is well drained by deep channels, only wild cane and a few groups of trees grow. Passing by many villages, whose huts were so isolated and concealed that they might remain unobserved, we arrived at five o’clock at Tagunton; from which a road, practicable for carabao carts, and used for the transport of the abacá grown in the district, leads to Goa; and here, detained by sickness, I hired a little house, in which I lay for nearly four weeks, no other remedies offering themselves to me but hunger and repose.

During this time I made the acquaintance of some newly-converted Igorots, and won their confidence. Without them I would have had great difficulty in ascending the mountains as well as to visit their tribe in its farms without any danger. When, at last, I was able to quit Goa, my friends conducted me, as the first step, to their settlement; where, having been previously recommended and expected, I easily obtained the requisite number of attendants to take into their charge the animals and plants which were collected for me.

On the following morning the ascent was commenced. Even before we arrived at the first rancho, I was convinced of the good report that had preceded me. The master of the house came towards us and conducted us by a narrow path to his hut, after having removed the foot-lances, which projected obliquely out of the ground, but were dexterously concealed by brushwood and leaves. A woman employed in weaving, at my desire, continued her occupation. The loom was of the simplest kind. The upper end, the chain-beam, which consists of a piece of bamboo, is fixed to two bars or posts; and the weaver sits on the ground, and to the two notched ends of a small lath, which supplies the place of the weaving beam, hooks on a wooden bow, in the arch of which the back of the lath is fitted. Placing her feet against two pegs in the ground and bending her back, she, by means of the bow, stretches the material out straight. A netting-needle, longer than the breadth of the web, serves instead of the weaver’s shuttle, but it can be pushed through only by considerable friction, and not always without breaking the chains of threads. A lath of hard wood (caryota), sharpened like a knife, represents the trestle, and after every stroke it is placed upon the edge; after which the comb is pushed forward, a thread put through, and struck fast, and so forth. The web consisted of threads of the abacá, which were not spun, but tied one to another.

The huts I visited deserve no special description. Composed of bamboos and palm-leaves, they are not essentially different from the dwellings of poor Filipinos; and in their neighborhood were small fields planted with batata, maize, caladium and sugar-cane, and enclosed by magnificent polypody ferns. One of the highest of these, which I caused to be felled for the purpose, measured in the stem nine meters, thirty centimeters; in the crown, two meters, twelve centimeters; and its total length was eleven meters, forty-two centimeters or over thirty-six feet.

A young lad produced music on a kind of lute, called baringbau; consisting of the dry shaft of the scitamina stretched in the form of a bow by means of a thin tendril instead of gut. Half a coco shell is fixed in the middle of the bow, which, when playing, is placed against the abdomen, and serves as a sounding board; and the string when struck with a short wand, gave out a pleasing humming sound, realizing the idea of the harp and plectrum in their simplest forms. Others accompanied the musician on Jews’ harps of bamboos, as accurate as those of the Mintras on the Malay Peninsula; and there was one who played on a guitar, which he had himself made, but after a European pattern. The hut contained no utensils besides bows, arrows, and a cooking pot. The possessor of clothes bore them on his person. I found the women as decently clad as the Filipino Christian women, and carrying, besides, a forest knife, or bolo. As a mark of entire confidence, I was taken into the tobacco fields, which were well concealed and protected by foot-lances; and they appeared to be carefully looked after.

In the afternoon we reached a vast ravine, called “Basira,” 973 meters above Uacloy, and about 1,134 meters above the sea, extending from south-east to north-west between lofty, precipitous ranges, covered with wood. Its base, which has an inclination of 33°, consists of a naked bed of rock, and, after every violent rainfall, gives issue to a torrent of water, which discharges itself violently. Here we bivouacked; and the Igorots, in a very short time, built a hut, and remained on the watch outside. At daybreak the thermometer stood at 13.9°

The road to the summit was very difficult on account of the slippery clay earth and the tough network of plants; but the last five hundred feet were unexpectedly easy, the very steep summit being covered with a very thick growth of thinly leaved, knotted, mossy thibaudia, rhododendra, and other dwarf woods, whose innumerable tough branches, running at a very small height along the ground and parallel to it, form a compact and secure lattice-work, by which one mounted upwards as on a slightly inclined ladder. The point which we reached was evidently the highest spur of the horseshoe-shaped mountain side, which bounds the great ravine of Rungus on the north. The top was hardly fifty paces in diameter, and so thickly covered with trees that I have never seen its like; we had not room to stand. My active hosts, however, went at once to work, though the task of cutting a path through the wood involved severe labor, and, chopping off the branches, built therewith, on the tops of the lopped trees, an observatory, from which I should have had a wide panoramic view, and an opportunity for taking celestial altitudes, had not everything been enveloped in a thick mist. The neighboring volcanoes were visible only in glimpses, as well as San Miguel Bay and some lakes in the interior. Immediately after sunset the thermometer registered 12.5°.

On the following morning it was still overcast; and when, about ten o’clock, the clouds became thicker, we set out on our return. It was my intention to have passed the night in a rancho, in order next day to visit a solfatara which was said to be a day’s journey further; but my companions were so exhausted by fatigue that they asked for at least a few hours’ rest.

On the upper slope I observed no palms with the exception of calamus; but polypodies (ferns) were very frequent, and orchids surprisingly abundant. In one place all the trees were hung, at a convenient height, with flowering aërids; of which one could have collected [205]thousands without any trouble. The most beautiful plant was a Medinella, of so delicate a texture that it was impossible to preserve it.

Within a quarter of an hour north-east of Uacloy, a considerable spring of carbonic acid bursts from the ground, depositing abundance of calcareous sinter. Our torches were quickly extinguished, and a fowl covered with a cigar-box died in a few minutes, to the supreme astonishment of the Igorots, to whom these phenomena were entirely new.

Farewell to mountaineers. On the second day of rest, my poor hosts, who had accompanied me back to Uacloy, still felt so weary that they were not fit for any undertaking. With naked heads and bellies they squatted in the burning sun in order to replenish their bodies with the heat which they had lost during the bivouac on the summit; for they are not allowed to drink wine. When I finally left them on the following day, we had become such good friends that I was compelled to accept a tamed wild pig as a present. A troop of men and women accompanied me until they saw the glittering roofs of Maguiring, when, after the exchange of hearty farewells, they returned to their forests.

From barometrical observations—

Goa, on the northern slope of the Isaróg

32

Uacloy, a settlement of Igorots

161

Ravine of Baira

1,134

Summit of the Isarog

1,966

Blogger's note: Given his description of the summit being 1966 MASL, he must reached the exact peak that we now reach after going up the Panicuason Trail. Like any mountaineer today, he must have been disappointed with the lack of learning at the top! Reference: The Former Philippines Through Foreign Eyes (Craig, 1917 ed.). Available: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/10770/10770-h/10770-h.htm#xd20e3939

FEDOR JAGOR'S HIKES IN BICOL (1859-1860)Hiking in Philippine history #1: Mt. Isarog

Hiking in Philippine history #2: Mt. Asog

Hiking in Philippine history #3: Mt. Masaraga

Hiking in Philippine history #4: Mt. Mayon